Redlining Was Outlawed in 1968, Why Hasn’t Home Lending to Communities of Color Improved?

Home lending is critical for communities of color to build generational wealth through homeownership. Yet, access to home loans continues to be out of reach for many of those that are Black, Indigenous, or people of color, thanks to the lingering legacy of redlining.

To understand why communities of color face these disparities, The Greenlining Institute has analyzed California’s annual home lending data reported under the federal Home Mortgage Disclosure Act for the past six years. Each year, we’ve found that communities of color do not access home loans at the same rate as their white counterparts, with very little or no improvement each year. One thing that is abundantly clear from our analysis: without intentional action from both policymakers and lenders, we should expect racial disparities in home lending to continue.

Below, we break down key findings from our latest report, Home Lending to Communities of Color in California 2021, and our recommendations for how to address lending disparities against the backdrop of our evolving financial system.

California Home Lending Trends

Unpacking Greenlining’s 2021 Home Lending Analysis

Key findings from our latest analysis of home lending in California include:

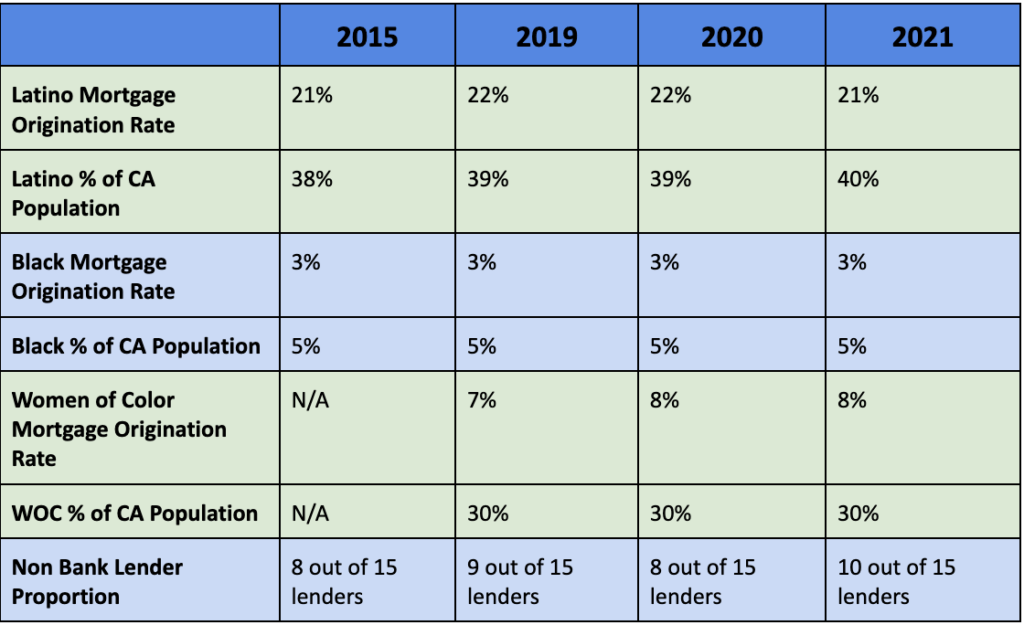

- Communities of color do not access home purchase loans at rates comparable to white communities. Latino households access 21% of the state’s home purchase loans, despite making up over 40% of the population, and Black households access 3% of home loans, while making up over 5% of the population. White households are especially overrepresented in home purchase originations relative to their share of the population, and Asian households are slightly overrepresented.

- Women of color, 30% of the state’s population, receive just 8% of home purchase loans by the top 15 lenders in the state, consistent with 2019 and 2020. Women of color are also more likely to access a loan from a nonbank lender than from a mainstream bank. The disproportionate caretaking burdens and responsibilities of women of color are compounded by the gender pay gap and racial wealth gap—all of which are compounded by an inability to access home loans.

- Asian ethnic communities do not access home loans at the same rate. While home lending to all Asian households in California appears to exceed their share of the population—rising to 19.4% in 2021 from 15.5% in 2020—there are disparities in access for different subgroups within the Asian population, emphasizing the need to collect and disaggregate lending data.

- Nonbank lenders are more likely to make home loans to low-income borrowers than traditional banks — with both conventional and government-subsidized loans.

Since we’ve started our annual HMDA analysis, home loan originations to Latinx and Black borrowers have remained steady at 21-22% and 3% respectively. But what has changed is the percentage of nonbank lenders that make up the top lenders in the state, rising from eight of the top 15 mortgage lenders in 2015 to ten in 2021. In 2020, 68% of all mortgages originated in the United States were issued by nonbank lenders, marking their highest market share on record.

Keeping Up with Shifts in Our Financial System

Financial institutions are responsible for making decisions about who can access mortgages based on federal regulations, financial risk, and fairness. This role has historically fallen on traditional banks; however, today, less regulated nonbank online lenders are increasingly taking over mortgage lending in California.

In addition, the U.S. financial system has changed significantly in the past few decades, and shows no signs of slowing down. More mergers and acquisitions in the banking sector have resulted in a smaller number of larger banks, each serving a greater number of people. Mergers between traditional banks and nonbanks are predicted to increase as traditional banks seek to expand their markets, increase fee revenue to offset lower rates, and enhance their digital capabilities. And now, we’ve seen regional banks – like Silicon Valley Bank – collapse and require rescuing by larger banks.

Our concern with all this change? That banks that are already less likely to make home loans to communities of color and low-income communities will tighten their lending even more, reducing access to safe and affordable home loans for already vulnerable communities.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has already caused a disruption in access to capital and investments for communities of color. Eleven affordable housing projects are at risk of losing funding and questions about the continuation of a community benefits agreement negotiated by community-based organizations remain unanswered. Communities across California stood to benefit from $1.3 billion in residential mortgages to low-income borrowers and borrowers in low-income census tracts, the expansion of a critical first-time homebuyer program and a Special Purpose Credit Program for BIPOC borrowers.

Those essential commitments to housing are a result of banks’ obligations to the Community Reinvestment Act. Nonbank lenders are exempt from the requirements of the Community Reinvestment Act, a federal law passed in 1977 to reverse redlining and meet the credit needs of low-to-moderate income communities. CRA is critical for obligating banks to meet the needs of low-to moderate income borrowers and, although race-blind, is an important tool for addressing the widening racial wealth gap and increasing access to first-time homeownership.

Building Accountability into Financial Regulations

A key recommendation outlined in our report is the creation of a California Community Reinvestment Act. Nonbank lenders should have the same mandate to serve low-to-moderate-income communities as traditional bank lenders, and this mandate can come from the state. A state CRA can expand beyond the many limitations of the current federal law. State governments in Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York have already passed state CRA legislation.

The financial institutions our communities must rely on to build wealth and security for their families need additional accountability. Currently, nonbank lenders are more likely to make loans to communities of color, but they are significantly under regulated, we have less information about their activities, and they have no obligations to make safe loans or reinvest in the communities they profit from.

As inflation, rising interest rates, and the worsening climate crisis continue to rock our financial system, now is the time to ensure we have the common sense regulations necessary to protect communities of color from pervasive economic barriers in our financial system. By investing in our communities, addressing systemic barriers to wealth-building, and narrowing the U.S.’s longstanding racial wealth gap, we can begin to unlock a thriving, resilient economy that works for everyone, not just a privileged few.