FCRA and Find Out: How Online Lenders Use Alternative Credit Scores to Prey on Communities of Color

Communities of color have long been targets of discriminatory lending. Now, in the new digital age, that discrimination has gone online.

Alternative credit scoring is the act of predicting credit worthiness using alternative data points. Namely, our online behavior — what we search, where we shop, even who we connect with. Data brokers collect and sell this information to third parties who eventually determine our access to loans, housing, jobs, and more. But these data points don’t tell a complete story — and, often, the incomplete and biased data used to train algorithmic decision-making systems will generate results that repeat deeply rooted, systemic inequities. Without responsible consumer protections, this data becomes the fuel to the fire for predatory lending, discriminatory marketing, and surveillance pricing.

How it works.

You’re browsing through your social media feed and see an advertisement pop up for the panini press in the exact shade of green to match your kitchen. You think, “Oh, what the heck? I deserve this,” and you enter your payment information. With a quick swipe, you’ve satisfied your need for retail therapy and got yourself a lovely new appliance for your apartment. You’ve taken the bait.

As this transaction is processed, in real time data brokers are extracting tons of raw data about you: your device type, geolocation at the time of purchase, any other advertisements you may have lingered on, time spent scrolling, and more. These data points are stitched together to create inference profiles: ‘Frequent Shopper,’ ‘Propensity for Impulsive Decision-Making,’ ‘Asian American Woman in Mid-Twenties,’ ‘Susceptible to Online Advertisements,’ ‘College-Educated and Lives Alone,’ and the list goes on.

Seems harmless enough, right? That is, until these data brokers start making inferences such as ‘Single Mother of Two, Union Member,’ ‘Middle-Aged Man with Clinical Depression,’ or even ‘Daughter Killed in Car Crash.’ A little invasive but, hey, I’ve got nothing to hide, right?

Well, now imagine being denied a job because your search history suggested you were an expecting mother. Or having your rental application denied because you downloaded a Muslim prayer app?

What if you were offered a higher interest rate for your mortgage application simply because you were a Black first-time home buyer and the algorithm determined you were more likely to accept the higher offer?

This is today’s reality of online surveillance and digital banking. From online behaviors to real world transactions, data brokers pick our lives apart and send them over to banks to determine the economic opportunities we have access to.

Each of these algorithmic systems — inferencing, alternative credit scoring, price-fixing — have the potential to reinforce bias against communities of color. It all comes down to the data — data about us, our communities, our spending habits, our vulnerabilities. If left unregulated, this emerging entanglement between data and lending will only amplify inequitable impacts of the racial wealth gap.

An Alternative to What?

For over 50 years, Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion have dominated credit reporting. These Credit Reporting Agencies, or CRAs, compile information on consumers’ financial data – such as their income, debt history, and length of loans – to determine consumers credit worthiness, influencing access to loan approvals, credit cards, rental applications, job opportunities, and more. CRAs are regulated by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, or FCRA, to encourage transparency, fairness, and nondiscrimination. FCRA ensures consumers can access and dispute the information used by CRAs — especially when those reports are sold to banks to inform a lending decision.

But newer fintech companies like Square, Chime, Venmo, and SoFi are now turning to alternative credit scoring. These models feed alternative data points – like transaction history, rent payments, gig economy income, spending patterns, and online activity – into algorithms to determine consumers’ creditworthiness. The pitch is that this expansion of data allows online lenders to provide loans to people that traditional banks may have overlooked. This includes the roughly 28 million credit-invisible consumers in the US, such as new immigrants, gig economy workers, Black and Hispanic consumers, and low-income, underbanked communities.

In practice, it’s not so simple.

Some alternative data points can indeed be used strategically and intentionally to promote financial inclusion. But using broad consumer data points – such as social media activity, biometric data, or search history – to determine credit worthiness opens the door to invasive surveillance and potentially harmful algorithmic bias. Even worse, the data brokers and fintech companies that collect and use this data are subject to significantly less regulatory scrutiny than traditional CRAs and banks. This means most people don’t know what data is being collected about them, how it’s being used, or how to correct it when it’s wrong.

From Data to Discrimination.

We know that seemingly neutral data points can still inform discriminatory outcomes. Algorithms simply reflect the biases in the data they are trained on. Because the reality for marginalized groups in our society remains deeply inequitable – for example, communities of color continue to face higher barriers to opportunity and the worst consequences of societal threats like climate change and economic instability – it follows that data collected on these groups will often reflect this inequity, rather than inherent consumer behaviors. Garbage in, garbage out.

Such was the case when a man in Atlanta received a demerit on his American Express credit card for shopping at a liquor store. In formerly redlined communities of color where grocery options are limited, a liquor store may be one of the few accessible options. But when every spending habit is scrutinized without considering this context, an algorithm might assume that everyone in that neighborhood is “financially risky” based on where they are shopping, leading to higher rates of denials for essential financial services. Unchecked, this surveillance risks recreating the same discriminatory patterns established by redlining.

This lack of context is also the reason automated home-valuation models continue to undervalue properties owned by Black homeowners in formerly redlined neighborhoods. A low rate of Black homeownership – the consequence of economic exclusion – in the data skews the inferences made by mortgage approval algorithms, which are 80% more likely to reject Black applicants for home loans. The broad use of alternative credit data increases the likelihood these models will perpetuate these types of discriminatory biases.

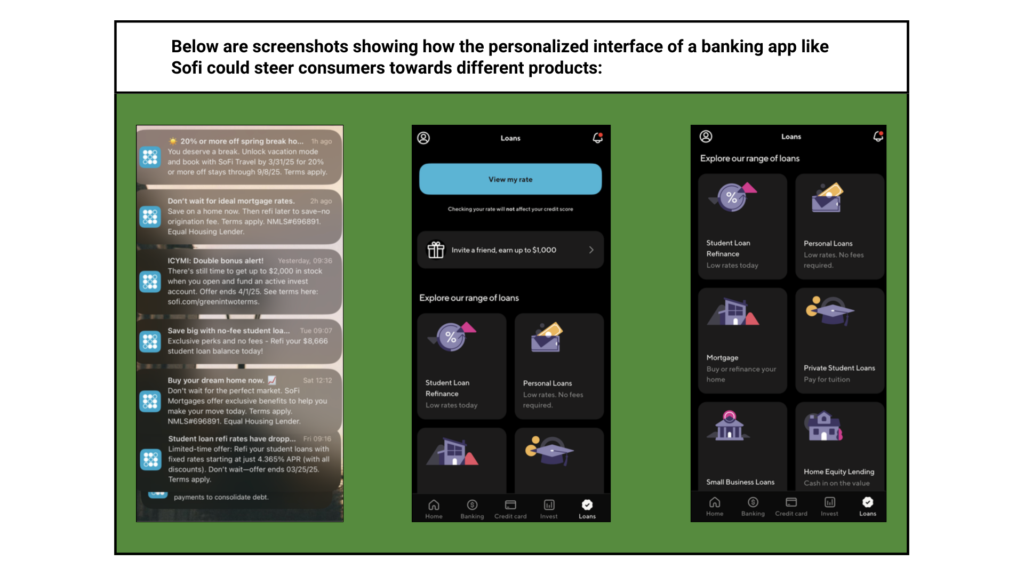

Even beyond credit scores, alternative data can be used to shape what ads people see, what financial products are marketed to them, and what prices they’re offered, enabling potential discriminatory marketing and price-fixing practices. Practices like “steering” on digital banking apps, for example, can push vulnerable consumers towards more expensive products; they do this by algorithmically manipulating product visibility, pushing personalized loan interest rates, and distorting the prices of similar financial products. On average, this leads to fintech lenders offering Black borrowers interest rates that are 5.3% higher than white borrowers.

FCRA and Find Out.

Under FCRA, when a traditional lender takes adverse action based on your credit report – this can mean getting denied for a credit card, failing a background check for a job, or having your rental application rejected – you have the right to see that report and dispute any errors. This process is critical to maintaining fairness, transparency, and nondiscrimination.

But data brokers and fintech lenders operate in a largely unregulated gray area. When your data is scraped and sold by data brokers to fintechs, you don’t know what they know and how they’re using it to shape your financial future. And you have no way of challenging it.

In December 2024, the CFPB proposed a rulemaking process to amend the FCRA and include data brokers in the definition of ‘Credit Reporting Agency.’ If passed, data brokers involved in lending would be subject to significant regulatory oversight for the first time in federal history. This was a landmark move in the expansion of fair lending in the online banking space. The Greenlining Institute submitted this comment letter in support of the ruling.

But since the beginning of the Trump Administration in 2025, the CFPB has come under direct attack. From the removal of former Director Rohit Chopra to the illegal cease-order forbidding federal employees from executing their administrative duties, the CFPB has been left toothless. The ruling will likely fail and, with it, any attempts to enforce the federal regulation of data brokers.

What Now? States Must Step Up.

As with so many civil rights protections under attack in this administration, the responsibility to protect Americans falls to the states. In states like California, the California Privacy Rights Act creates a registry of data brokers collecting personal consumer data in the state, allows users to opt out of data collection, and makes it possible to request data brokers to delete their personal data. These laws have inspired similar legislation in other states like Virginia, Colorado, Nebraska, and Vermont.

We are entering a new era defined by the techno-industrial complex — where a handful of powerful tech billionaires wield enormous influence over our civil rights, economic opportunity, and privacy. If policymakers, regulators, and other key decision-makers fail to act, we risk allowing these tech billionaires to automate discrimination at an unprecedented scale. Now is the time to push forward with eyes wide open. At Greenlining, we know equity will not just happen — it’s a practice that starts with commitment, transparency, and accountability. By supporting federal agencies like the CFPB and enacting protective, forward-looking privacy legislation at the state level, we can hold our ground. But we need leaders and policymakers to step up.

The future of economic equity will be decided, not just in courtrooms or elections — but in data sets, algorithms, and APIs. Together with policymakers, we can ensure the path forward doesn’t repeat the harms of the past. We can forge a path towards equity and economic empowerment for communities of color.