Driving Towards Equity: Ensuring Clean Air and Accessible Transportation for All Californians

California has taken bold action to reduce transportation pollution, including banning the sale of gas vehicles starting in 2035. And with good reason. Six of the 10 most polluted cities in the nation are in California, while 50% of greenhouse gas emissions and 80% of nitrous oxide emissions come from transportation.

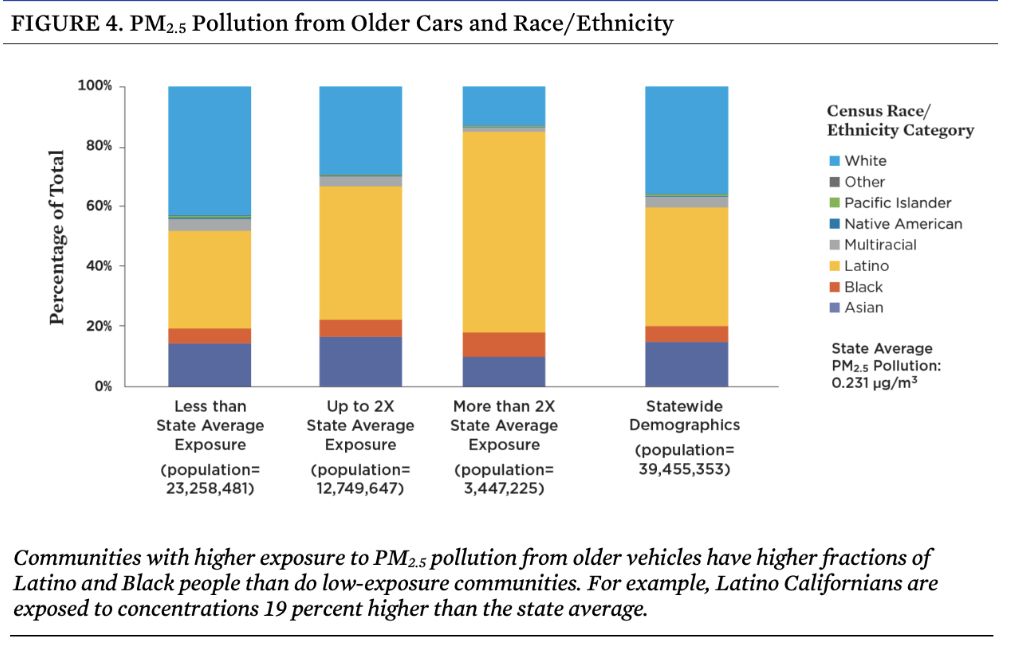

The consequences of transportation pollution are not borne equally among Californians. Due to a long history of racist government planning and policies, low-income communities and communities of color have been targeted for highway projects that cut through their neighborhoods, saddling them with excessive pollution.

Redlining and disinvestment has long stifled economic growth in these same communities, leaving them with longer commutes that can hinder the ability to reach employment opportunities and centers of economic opportunity. Today, communities that are disproportionately Black, Latino, and low-income endure the worst rates of pollution, and at the same time tend to be more reliant on older gas-powered passenger vehicles due to the high costs of switching to newer, cleaner forms of transportation.

In addition to driving the harmful impacts of climate change, gas- and diesel-powered vehicles produce fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which has been shown to cause negative health impacts. Short-term exposure to PM2.5 can cause eye, nose, throat, and lung irritation, negatively impact heart and lung function, worsen heart disease and asthma, and increase the risk of heart attack.

Daily and long term exposure has been linked to increased mortality rates from heart disease and may be associated with increased rates of chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function, and lung cancer. The risk of pediatric asthma is increased for children who experience higher exposure to pollutants from vehicles. All of these negative health impacts are disproportionately borne by low-income Black and Latino communities.

All of these negative health impacts are disproportionately borne by low-income Black and Latino communities.

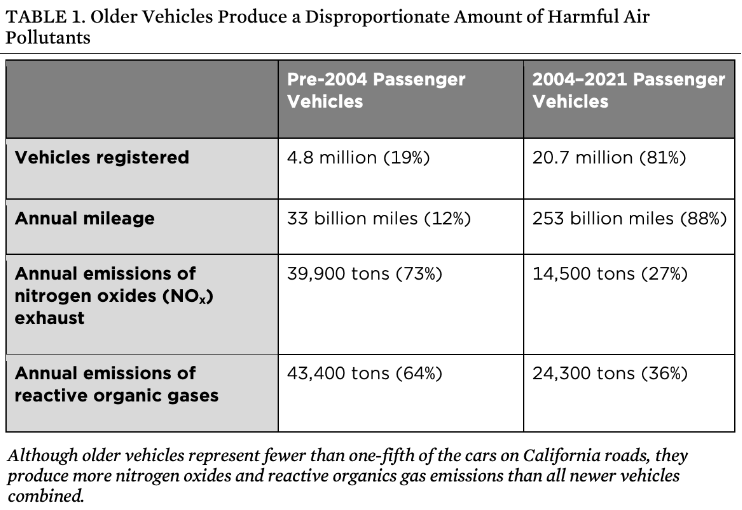

In 2004, California implemented stronger emissions standards that decreased the amount of health-impacting pollutants a car could emit. In a recent study The Greenlining Institute conducted with the Union of Concerned Scientists, Cleaner Cars, Cleaner Air, we found that despite accounting for only 12% of the miles driven by cars, cars made before 2004 contribute to 73% of Nitrous Oxide, a pollutant that forms PM2.5. These older cars are concentrated in lower-income communities with higher percentages of Black and Latino residents. On average, white Californians and higher-income households face far lower exposure to PM2.5 from older cars. Emissions from these older cars lead to as many as 421 premature deaths per year.

On top of the health impacts, these communities experience economic impacts due to decreased reliability and higher maintenance and fueling costs. Replacing gas- and diesel-powered cars with zero emission vehicles – including electric vehicles – reduces pollution exposure for communities they are in. With historic investments from California in zero emission vehicles, this is the direction we’re headed in. But with the high cost of EVs and a lack of clean transportation infrastructure investments in low-income communities of color, California’s transition runs the risk of leaving communities behind.

But with the high cost of EVs and a lack of clean transportation infrastructure investments in low-income communities of color, California’s transition runs the risk of leaving communities behind.

What would it mean to transition equitably?

California is leading the nation in the transition to EVs. EVs provide tangible health benefits for communities because they don’t produce tailpipe emissions. EVs also have lower maintenance and fueling costs than a gas car. Widespread adoption will lead to cleaner air and have positive health impacts for the entire state. But to make this transition equitable and effective, the state must prioritize the communities that endure the worst pollution burdens and face the highest barriers to making the switch. If we leave low-income communities of color behind, we will not only worsen existing inequities, but we won’t meet our climate goals.

Yes, EVs are becoming increasingly affordable, yet they are still out of reach for the majority of Californians. According to Kelley Blue Book, the average cost of a new EV in February 2023 was $58,385, nearly $10,000 more than the average new vehicle price of $48,763. The average cost of a used EV was around $43,400 in March 2023, according to Forbes. The most affordable EVs, the Chevy Bolt EV or EUV, will end production at the end of 2023. A quick calculation for a Californian making the median income ($68,000 per year) spending the recommended 15 percent of their income over a 4-year loan on a car payment can afford a $30,000 car. Even with the $7,500 federal tax credit, EVs are unattainable for more than half of the state. In addition to cost being a barrier to access, access to reliable and convenient charging is also an issue in low-income communities and communities of color.

Stronger equity programs and policies are needed now

For those who are breathing in pollutants from transportation each day, cleaner cars are not reaching their communities fast enough. California is a national leader in the transition to zero emission vehicles and as such, we have a responsibility to implement community-centered equity programs that serve as a model for other states as they adopt their own incentive programs.. Given the need for faster EV adoption and the state’s limited resources, The Greenlining Institute offers these policy recommendations that can help existing state programs prioritize where these investments go and address the disproportionate health impacts of older cars on communities of color:

- Prioritize incentives toward priority populations that own higher percentages of these pre-2004 cars. If we target the limited dollars available for EV incentive programs, such as Clean Cars 4 All and the Clean Vehicle Assistance Programs, towards these communities, we will see direct impacts on health and cleaner air. We recommend that CARB prioritizes incentives to households who are low-income, in disadvantaged communities and that own a pre-2004 vehicle in order to maximize economic and public health benefits.

- Target outreach and education to areas with high concentrations of old cars and limited uptake of zero-emissions vehicles. State and local agency outreach should be sensitive to the fact that older-car pollution disproportionately burdens Latino and Black communities. Multilingual and culturally accessible outreach and education are essential, and collaboration with trusted community-based organizations can ensure that these communities have greater access to zero-emission vehicles. We recommend that CARB’s outreach efforts target households who own these vehicles by working closely with their program administrators and the California Department of Motor Vehicles.

- Invest in transportation and mobility solutions that go beyond private passenger vehicles that address the unique needs of these communities. Even as California seeks to reduce vehicle miles traveled, the state continues to invest in highway expansion and vehicle incentive programs that prioritize car ownership. Agencies should prioritize funding for programs that promote alternative modes of transportation, such as electric bikes, electric car sharing, and public transportation. One option is to dedicate more funding and increase the amount for the alternative mobility option component of Clean Cars 4 All to encourage more households to access other forms of mobility. Programs like Clean Mobility Options and the Sustainable Transportation Equity Program – which have both long been underfunded and use a bottom-up approach and enable communities to define their needs – are key programs that think beyond car ownership. This strategy could be particularly fruitful in the denser, urban hubs of greater Los Angeles where a substantial portion of older-vehicle pollution is concentrated.

The programs we implement in California hold the potential to impact communities of color beyond our state. Equitably-designed programs by design deliver more equitable outcomes and it’s not too late to adjust our own incentive programs to address the needs of our communities. As other states look to us when developing their own clean air strategies, we have the opportunity to model a process that doesn’t leave our most vulnerable communities behind, but instead centers them in our transition.