Capacity Building: Learning from the Communities that Raised Us

Top-Down & Ground-Up

To reverse decades of disinvestment and racist policies, we must double down on community ownership of the solutions. Communities know best what their neighborhoods need, but they still require additional resources, partnerships and technical expertise to bring these local visions to life.

That’s why the Greenlining Institute is building a team focused on centering capacity building in low-income communities of color. Greenlining’s capacity building team works to change the structural conditions–embodied in statewide policies and practices–from the top-down so that communities of color in California can thrive.

We’ve co-sponsored legislation like AB 2722 (Burke, 2016) and SB 1072 (Leyva, 2018) to create Transformative Climate Communities and Regional Climate Collaboratives–programs that invest in community capacity, partnerships and plans to fight climate change and build stronger, healthier, and economically resilient neighborhoods. Now, we’re making a renewed commitment to capacity building at the neighborhood level.

As part of our new Strategic Plan, launched in 2021, we created a new Capacity Building team dedicated to supporting under-resourced communities to gain equitable opportunity and access to tools to lead their own transformations. We define “capacity building” as the following:

CAPACITY BUILDING IS THE PROCESS OF STRENGTHENING LOCAL LEADERSHIP, SKILLS, EXPERTISE AND RESOURCES SO THAT COMMUNITIES CAN MEET THEIR NEEDS AND ACHIEVE SELF-DETERMINATION. AGAINST A BACKDROP OF SYSTEMIC DISINVESTMENT AND OPPRESSION, WE MUST INVEST IN THE CAPACITY OF LOCAL LEADERS TO ADVANCE COMMUNITY VISIONS. THIS WORK INCLUDES UPLIFTING COMMUNITY KNOWLEDGE, BUILDING SKILLS, DEVELOPING PARTNERSHIPS, IDENTIFYING AND PLANNING FOR PROJECTS, AND SHIFTING RESOURCES AND POWER.

We’re building off our experiences building capacity in support of environmental justice in South Stockton and creating a multi-state Community of Practice for equitable electric mobility. Now, we’re also working to support community leaders in Oakland and Los Angeles, two of California’s biggest cities. By expanding community capacity, we work towards community power-building, self-determination, and the ability of all communities to have ownership over the decisions that shape their lives.

To provide a peek into our growing strategy and practice, two of our program managers–Aminah Luqman and Katherine Cabrera–offer their perspectives on how they came to understand capacity building growing up in their own communities.

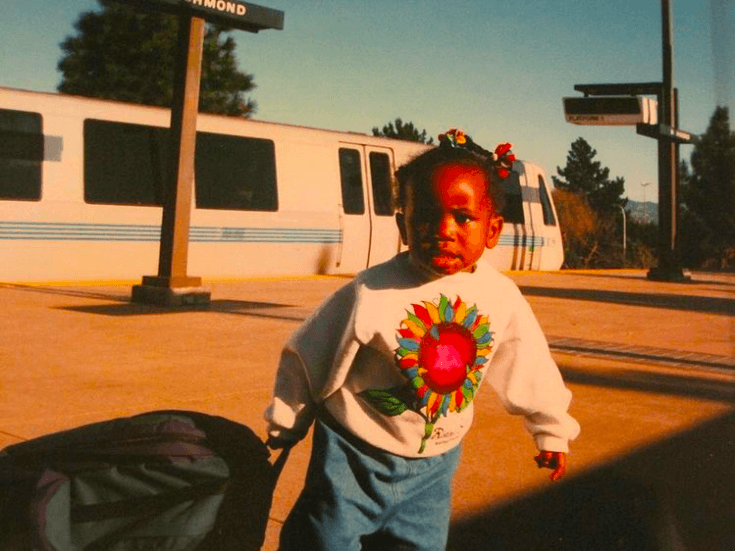

Capacity Building in Oakland – Aminah Luqman

Capacity building is one of those terms that mean everything and nothing at the same time. For the most part, people understand capacity as a concept (e.g. I don’t have the capacity to take on this project right now). However, the numerous factors that contribute to why someone may not have capacity makes the term “capacity building” nebulous.

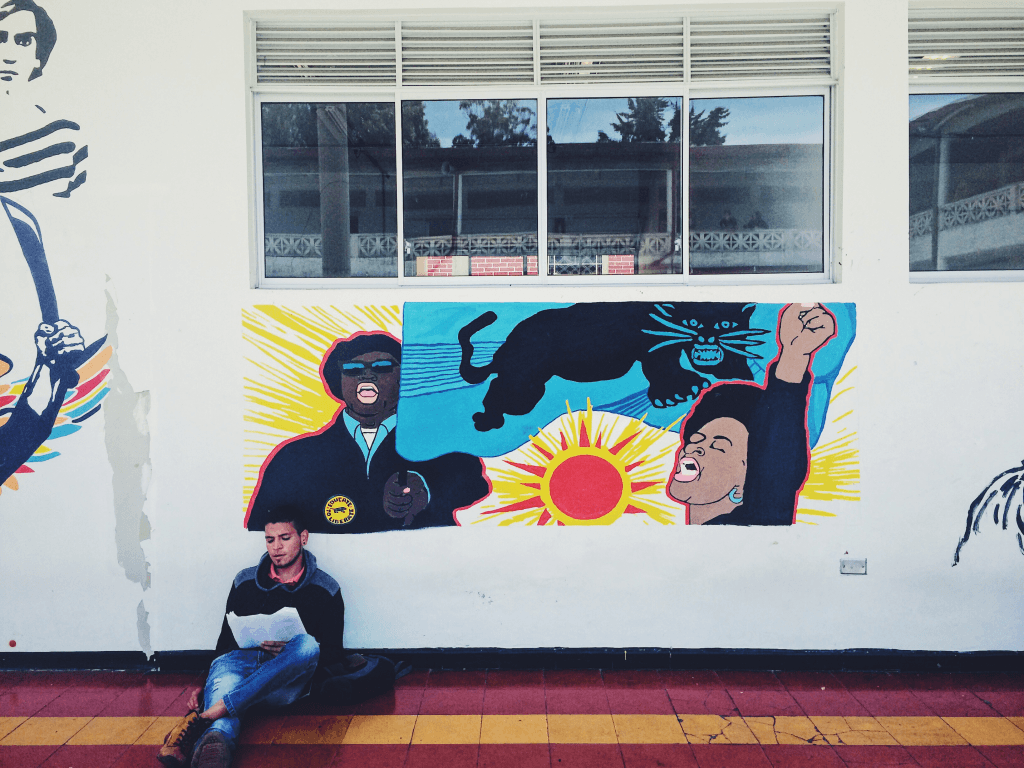

Though I didn’t always have a word for it, I’ve come to realize that I’ve seen the work of capacity building all my life in my hometown of Oakland, California. When I think about the things I love about Oakland, I think about the iterative and interconnected processes of residents taking matters into their own hands and forming powerful collectives to build healthy and thriving communities. I think about the Black Panther Party and all the ways their work and members have influenced organizing efforts in Oakland and the world. I think about Tall Paul, who offered to make me a scraper bike in exchange for good grades in 2014, and the Scraper Bike Team now advancing youth empowerment, clean mobility and climate change mitigation the Oakland way. I think about the blue “Build a Black Cultural Zone” sign I saw at EastSide Arts Alliance’s Malcolm X Jazz Arts Festival in 2015 and the fact that I can attend the Black Cultural Zone’s bustling Akoma Market in 2022. These are all examples of what is possible through capacity building.

Too often frontline communities-those hit first and worst by the impacts of climate change-are cut out of the process of making decisions about how to best mitigate, prepare for, weather and adapt to the effects of climate change. Instead, people who are not from or of the community piece together solutions on community members’ behalf. These practices lead to inaccessible, unhelpful or even harmful outcomes that could have been avoided if communities’ lived experiences, needs and leadership were valued, centered and prioritized from the start.

Like many other places in the United States, certain neighborhoods in Oakland (namely Chinatown and neighborhoods in East and West Oakland) were systematically designed and designated to be the most environmentally polluted. Consequently, the Oakland residents who live, work, play and grow in these neighborhoods are experts in identifying the harms done to their communities, as well as building the types of neighborhoods in which they want to live. As evidenced by community plans like the West Oakland Community Action Plan (WOCAP), the East Oakland Neighborhood Initiative (EONI) plan and the Oakland People’s Plan, the expertise and vision is there.

Oakland residents have been doing important placemaking and legacy-building work for better, healthier and cleaner communities for decades. In my eyes, engaging in capacity building work is about supporting and fostering these existing efforts and bolstering the capacity needs that have been weakened or hindered through disinvestment, redlining, and other forms of systemic discrimination and racism.

While our team’s capacity building work focuses on climate change, climate justice is just one piece of an interconnected puzzle. Affirming and upholding housing and access to clean air and water as a human right is also capacity building. Good paying jobs that value workers’ skills, safety and dignity is capacity building. Access to affordable and quality healthcare and wellness resources is capacity building. Transportation systems that allow people to go where they need and want to go without breaking the bank or experiencing harassment and violence is capacity building. This is why Greenlining is committed to desiloing our policy work and building capacity from the top-down as well as the ground-up. As we collectively work to build people power and advance community visions, it’s important that we also address the systemic issues that made capacity building a need in the first place. This work will require all of us, as well as a commitment to the long term, but I’m lucky and excited to be able to do it in the city that showed me it’s possible.

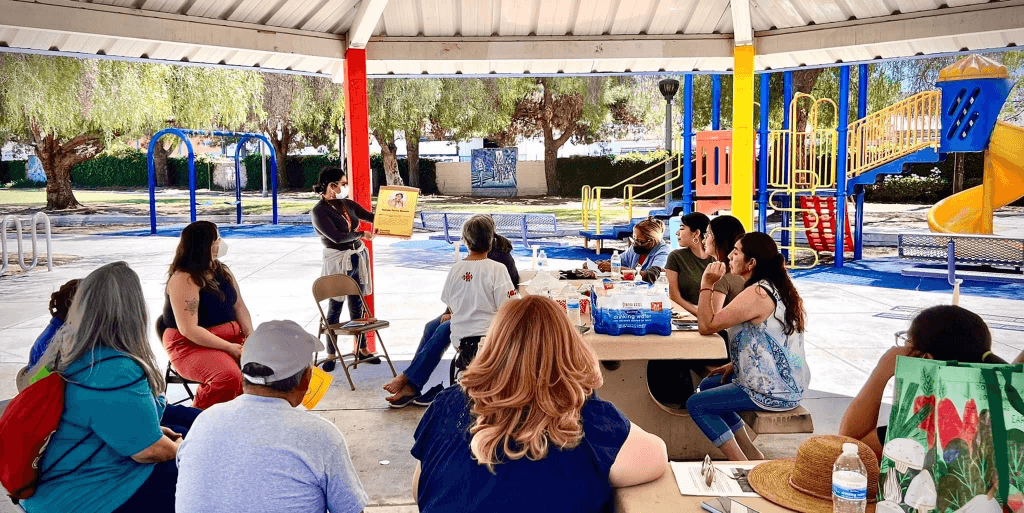

Capacity Building in Southern Ca – Katherine Cabrera

When I joined Greenlining this past summer, capacity building was a relatively new term for me. I’ve since learned that capacity building means equipping communities with the resources, tools and partnerships needed to realize their own community visions. In doing so, we acknowledge that this is part of a larger path towards systems change and addressing systemic inequities. Lately, I’ve reflected on how growing up in the Inland Empire informs my understanding of capacity building:

“Reten Adelante (checkpoint ahead)” was a phrase I constantly saw throughout my teenage years. My mother, who worked at our local parish in the City of Ontario, would print flyers with this phrase on them. She would ask me to hang the flyers throughout the church to warn our parishioners who were predominantly undocumented. Unfortunately, for many, the warning was too late and their vehicles would get towed for driving without a license (pre AB 60). The majority didn’t have the financial resources to pay the fines to get their vehicles back and were left without transportation in an area with poor public transit.

At the same time, the goods movement expanded rapidly in the region. This led to an influx of precarious and low-wage jobs that included the use of surveillance and software technologies used to track workers’ production-a transformation described in Juan De Lara’s book, Inland Shift. In addition to facing unstable and exploitative economic conditions, my neighborhood is among the most polluted in the state. The City of Ontario alone has multiple census tracts designated in the top 5% of disadvantaged communities (CalEnvironScreen 4.0). It was through this that I saw the intersections of immigrant rights and environmental justice and how capacity building efforts cannot be siloed.

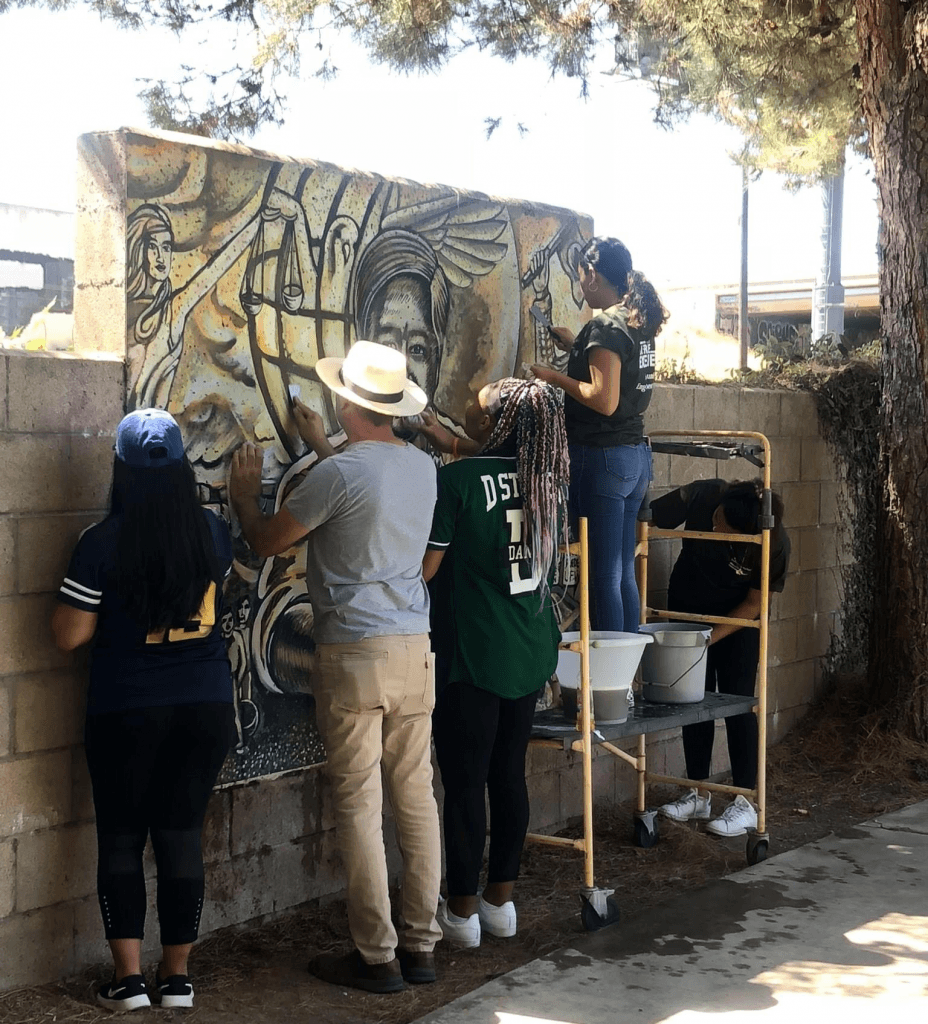

My community was impacted by xenophobic anti-immigrant laws, exploitative working conditions, environmental racism and resource scarcity. Yet, my community challenged these acts and organized. Genevieve Carpio, an ethnic studies scholar specializing in history, race, and the public humanities outlines these acts of resistance and placemaking in her book, Collisions at a Crossroads. Whether it was the Pomona Habla Coalition standing at street corners with signs to warn motorists of checkpoints ahead, the use of testimonios (workers’ stories) by warehouse workers to uplift organizing efforts, or the restoration of murals at Cesar Chavez Park as a way to address pollution, these actions all drive a process of reimagining alternative spaces for our immigrant communities.

These are the same communities that are at the forefront of fighting for climate justice, tenants’ rights and workers’ rights today. Huerta del Valle-a partner organization of the Transformative Climate Communities- established an urban farm, where my family and I are able to buy fresh produce in a neighborhood dominated by warehouses. Local community groups provided COVID-19 resources, vaccination clinics and mutual aid efforts throughout the pandemic. Our communities’ histories of resistance and placemaking show us what the future of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color can look like, and offer a first-hand account of how capacity building efforts can support them in achieving self-determination.

At Greenlining, our capacity building work is rooted in climate resilience and equity, but we also understand that our work needs to be intersectional. It needs to center the voices of all those who are at the margin and have been systemically disadvantaged. Capacity building means supporting and recognizing that the work that has been done by Black, Brown, Indigenous, and immigrant rights serving organizations is integral to achieving systems change. As we continue engaging in our capacity building efforts, I’m looking forward to uplifting and supporting a diverse set of community stakeholders, and engaging with those who have traditionally been excluded from the climate conversation.

Capacity Building in State Policies

Greenlining is excited to ground our capacity building efforts locally in California (Stockton, Oakland, LA) and across the country in Colorado, Illinois, Virginia, North Carolina and Michigan. At the same time, we are also intentionally integrating capacity building into our advocacy on California state policies.

The California Strategic Growth Council (SGC) recently launched the Regional Climate Collaboratives (RCC), a program Greenlining helped shape to develop the capacity of under-resourced communities to secure funding for climate change projects. Our goal is to support community members come together to deepen partnerships, engage residents, develop project ideas and ultimately secure funding for those community visions. The RCC program represents a significant acknowledgement of the importance of investing directly in communities, especially when the State is relying on local communities to advance its climate goals. It also builds upon SGC’s recent adoption of a resolution advancing capacity building as a key equity strategy for multiple State agencies.